Why You Got Bioelectricity Wrong

Why both the hype and the skepticism miss the point

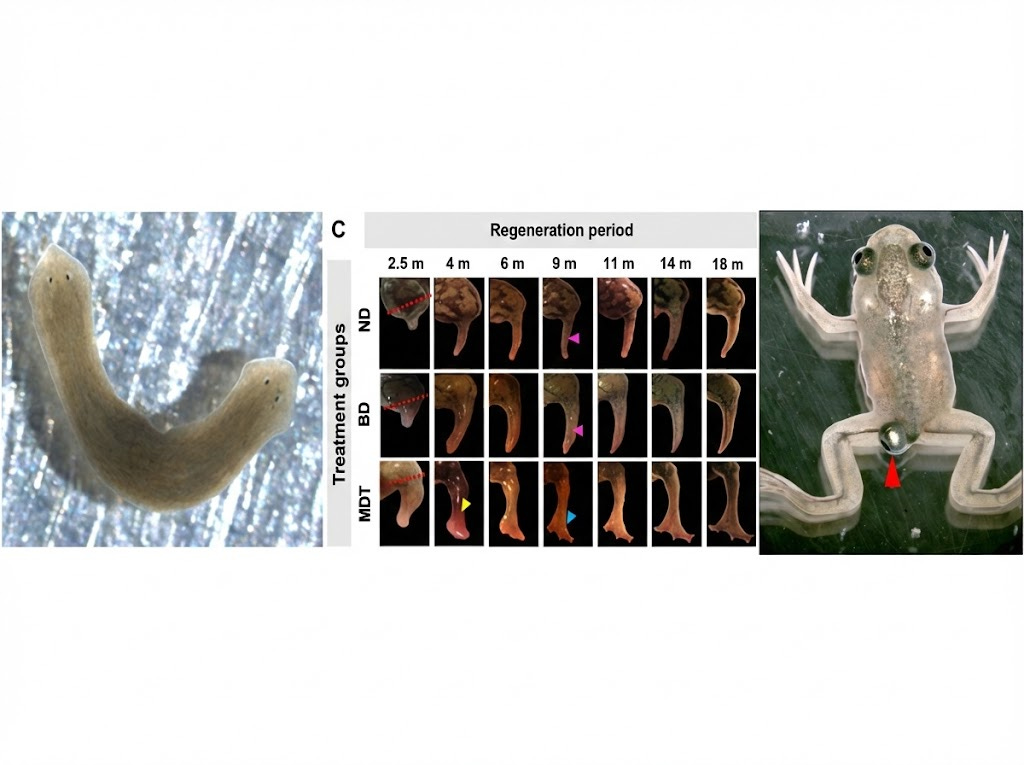

You have probably heard a lot about bioelectricity recently. Both the awe and criticism of the membrane potential has been storming through niche biology communities. This research direction has famously produced double-headed planaria, regenerated the limbs of frogs, and induced a functional eye on the butt. What if we could grow humans with two heads by simply changing the membrane potential during embryogenesis? Or solve aging by simply hyperpolarizing the cells?

If you are not familiar with bioelectricity, I recommend checking out this article or this paper. I’m frankly only going to do injustice to this topic by describing it in a few sentences here. Throughout this post, when I say ‘bioelectricity,’ I mean membrane potential (Vmem). Membrane potential is the voltage difference across a cell’s membrane, set by the balance of ions (sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium) flowing through channels embedded in the membrane.

Below are examples of what you can do by manipulating bioelectricity.

Changing the bioelectric pattern at a worm’s tail to match its head makes it grow another head.

Manipulating membrane potential in non-eye tissue to match the signature of eye progenitor cells induces a functional eye.

Exciting, isn’t it?

Most of the work on bioelectricity has been spearheaded by Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts who has done incredible work on the intersection of collective intelligence, regeneration, and synthetic life forms.

There are two camps of people: bioelectricity maximalists and bioelectricity haters. One believes that bioelectricity is the solution to all biological problems, another one dismisses it as a gimmick and fake science.

I believe that both camps are making the same mistake. They are treating bioelectricity as a standalone phenomenon, something that can be celebrated or debunked on its own terms. But bioelectricity does not exist in the vacuum. Thoroughly studying the work of Michael Levin made me realize that it is an instance of something fundamental, which requires reasoning through foundational questions first. What does it mean for an object to maintain its identity over time? How do perception and agency emerge from that constraint? Once you have that framework, the significance of membrane potential becomes obvious. And so do its limits.

From first principles, I will build a framework: from how objects persist as entities, to how cells coordinate without central control, to why electrical signals emerge as a natural intervention point. By the end, you should be able to derive the importance (and limits) of bioelectricity yourself. Most importantly, I hope this blog post inspires new ways to think about biomedicine.

How does anything exist?

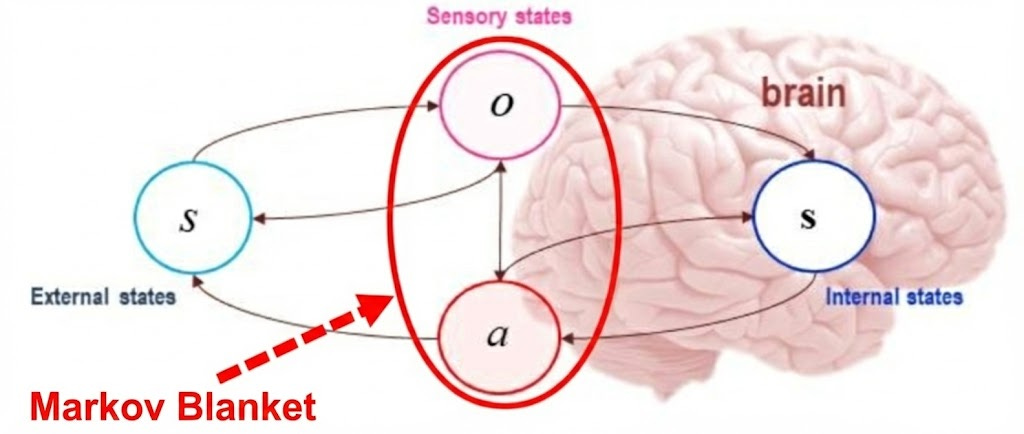

How do objects form in the universe? Seriously, when you look outside, you see a coherent table, a chair, and trees. For some reason they do not just bleed out and mix with the floor. You can clearly see objects like humans, which persist as stable units despite constant exchange of matter and energy with their surroundings. But there is one problem: you never perceive the world directly, and all perception is mediated by changes at the boundary between you and the environment. What you experience are patterns in neural signals produced by sensory transduction, not the objects themselves. You “see” the neural activity triggered by light interacting with your retina, not the screen itself on which you are reading this. The screen contains many interacting layers (electrons, molecular lattices, circuitry), but your sensory boundary compresses all of them into a coherent object. In short, the boundary constrains which correlations are recorded and acted upon.

Markov Blankets

To reason rigorously about these ideas, I need to introduce the concept of Markov blankets. I hinted at them in my previous blog post, though I avoided the formalization of boundaries between objects. Formally, there are four variables at play:

External states: air temperature, sound waves, light patterns, other people

Sensory states: retinal activation, cochlear vibrations, skin thermoreceptors

Active states: muscle contractions, speech, eye movements

Internal states: beliefs, memories, metabolic variables, neural activity patterns

Markov blankets naturally create a boundary between what is happening on the inside of the system, and the outside, which we can formally call conditional independence between the internal and external states. But what is the significance of this?

If you know the sensory and the active states (the Markov blanket), then knowing the external environment gives you no extra information about the internal state. Put differently, if I told you everything about the state of your retina, learning more about the screen itself would not change what your brain can infer, because all of that information is already compressed into the sensory signal.

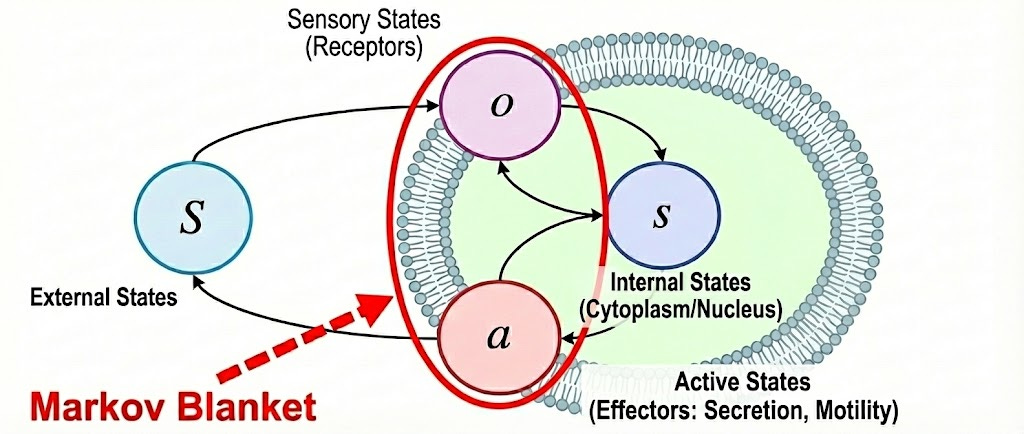

A Markov blanket is necessary since it allows an object to have a coherent view of what is happening outside. Without a boundary, a cell would have to track the position of every particle in the universe. The Markov blanket is what makes the problem finite.

So to summarize, a Markov blanket is what any system must have in order to persist as a distinguishable entity.

Agency

We have discussed how you perceive things, but what about actions? We know that observers do not just passively look at their environment. I have pointed out above that active states are also part of the blanket, but I have only focused on sensory states so far. Now it’s time to define agency.

Agency is the system changing the world through active states in a way that tends to reduce unexpected sensory states. The perception (part of Markov blanket) creates something circular:

Perception updates belief

Beliefs drive actions

Actions change what you perceive next

But what is meant by “surprise” here?

Formally, surprise is quantified as free energy:

While I am not going to get into the weeds of this equation, you can think of it as a system trying to decrease the unexpectedness of what it sees under its generative model. It is important to recognize the distinction between the generative model and the internal states. Internal states are the physical variables of a system (neural, biochemical, or mechanical states) that evolve over time and are shielded from direct external influence by the Markov blanket. A generative model is a description of how a system’s internal dynamics are organized so that it anticipates how its sensory states will change as a result of external influences and its own actions.

For example, in a chemotactic cell, internal biochemical concentrations change in systematic ways with receptor activation and the cell’s own movements. These internal dynamics bias flagellar motion so as to keep receptor activity within viable ranges, even though the cell contains no internal description of nutrients or gradients as such. The generative model is not a separate component inside the cell, but a pattern of cause and effect built into the cell’s biochemistry. The cell moves in ways that keeps receptor activation within familiar bounds, which limits unexpected sensory states without ever representing ‘nutrients’ or ‘gradients’ as such.

For a more in depth dive into all this I recommend reading this and this.

Internal Models

A crucial implication of this is that a system does indeed have a model of the environment, and has some belief of what is happening outside of it (it does not observe the ground truth due to the blanket) which it compares with its expectation. This is true for any system that persists as a distinguishable entity: a rock, a cell, a dog, or a human. Also it's important to keep in mind that a system can only influence the external world through its active states, just as it can only be influenced by the world through its sensory states. Perception and action are two sides of the same boundary defined by the Markov blanket.

Notice what all this implies. The system is not a machine that unfolds mechanically according to rigid rules. It is a closed loop. Sensory states update internal states, internal states drive active states, and active states change what the system senses next (see diagram above). The loop never opens. This is exactly why cells are not passive recipients of instructions, but agents inferring and acting on the world.

Multi cellular systems

Now, we are ready to scale this intuition to multiple cellular systems. Cells can not see inside each other, and each cell is effectively wrapped into their own Markov blankets. Your liver cell has no direct knowledge of what is happening inside your neurons. It only knows what it can sense at its boundary. And yet, somehow trillions of these isolated systems coordinate to produce you. There is no central controller, no master cell running the show. No single neuron contains your memories or your sense of self. What makes you you is not located in any particular cell. It emerges from the patterns of communication between cells, each updating its internal model based on signals received at its blanket, each broadcasting signals that arrive at the blankets of others.

Biomedicine

But how is this practical? In this framing the goal of biomedicine is to engineer the proper coordination between different levels of biological competencies (e.g cells, tissues).

One obvious way to approach this in biomedicine is to intervene directly on the internal model itself (through genetic modification or protein introduction), editing the system’s internal states. This strategy has dominated biology for decades and can be effective, but it treats internal structure as the primary control lever.

But consider aging. Your parents’ gametes were decades old at the time of your conception. The oocyte that became half of you had been sitting in your mother’s ovary since before she was born. By any reasonable definition, these are aged cells. And yet they gave rise to you: a young organism with fresh tissues, not an infant born with forty-year-old cells.

The genome in that oocyte was the same aged genome. What changed was the signaling environment. Fertilization and early embryogenesis create a specific bioelectric and biochemical context that resets cellular behavior. Young tissue grows from old cells, not because the cells were genetically rejuvenated, but because they received signals at their Markov blanket that told them to behave young.

This suggests an alternative strategy: instead of editing the internal states, intervene at the level of the blanket itself. The Markov blanket occupies a much lower-dimensional space than the system’s internal states. And there is a structured mapping from blanket states to internal state updates, even if the internal model itself is complex and opaque. If we can send the right signal to the boundary, the cell will update its own model accordingly.

The principle is familiar from everyday life. You do not need to install a chip in someone’s brain to change their political beliefs. Language does the job. Words are signals at the Markov blanket that update the internal model. The logical question for biomedicine: what is the language that cells speak?

Controlling the blanket

Once we accept the membrane as the intervention target, we face a choice. Cells sense electrical, mechanical, and chemical stimuli at their boundaries. Which modality should we use? We need a control signal that satisfies three constraints: fast enough to coordinate changes across the system, shared across many cells to enable coherent updating, and tightly coupled to downstream internal state changes.

Chemical

One option is to apply some chemical signal to the boundary, and hope there is going to be a lasting effect to the model. However, there are almost infinitely many small molecules out there with an incredible scale of possible concentrations. Unfortunately, we do not have a reliable way to measure the model (genes) in real time with spatiotemporal precision, which makes it complicated to build a map of relationships between the wide range of chemical stimuli and the internal model. Though obviously not impossible in the future.

Mechanical

Mechanical signals can influence cellular state through deformation, tension, and pressure. However, they fail our criteria in important ways. They propagate slowly, limited by the physical properties of tissue. They are highly local, since a mechanical force applied to one region does not easily coordinate behavior across distant cells. And their effects are context-dependent, varying dramatically based on tissue stiffness, cell density, and ECM composition. Lastly, mechanical inputs ultimately exert their influence by modulating ion channel activity at the membrane, meaning they mostly converge downstream on the electrical state rather than acting as an independent control variable.

Electrical

Electrical signaling satisfies all three constraints.

Speed: ion flux across membranes occurs on the millisecond timescale, orders of magnitude faster than diffusion-limited chemical signals or mechanically-propagated forces.

Shareability: cells are electrically coupled through gap junctions, allowing voltage changes to propagate across large cell populations as a coherent signal. A change in one cell’s membrane potential can influence thousands of neighbors almost instantaneously.

Tight coupling: membrane potential directly gates ion channels that control everything from gene expression to cytoskeletal dynamics to metabolic state.

The beauty of this finding is that a relatively simple signal, a measurable voltage difference across the membrane, triggers extraordinarily complex coordinated behaviors in cells. While double headed planaria is the frontrunner, let me focus on something less popular: bone healing and cancer.

Bone Healing via Electrical Fields

In 1957, Fukada and Yasuda discovered that bone is piezoelectric. When you put it under mechanical stress, it generates electrical fields. Areas under compression become electronegative and undergo resorption, while areas under tension become electropositive and produce new bone. So what if we could supply those signals externally?

The answer came through decades of clinical work. The FDA approved pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) stimulation for treating nonunion fractures in 1979. Today, nine FDA-approved electrical bone growth stimulators are commercially available. The clinical data is striking: PEMF treatment achieves healing rates between 73% and 89% in fracture nonunions that had previously failed to heal.

The mechanism operates through the Markov blanket. The external electromagnetic field induces weak electrical currents at the fracture site, typically between 1 and 100 mV/cm. These fields activate voltage-gated calcium channels at the cell membrane, triggering intracellular calcium signaling. This in turn upregulates production of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP-2 and BMP-4) and TGF-beta, promoting osteoblast activity and extracellular matrix synthesis. The cells did not need new genetic instructions. They needed the right signal at their boundary, which then propagated inward to shift their internal model toward bone building behavior.

Cancer as a Bioelectric Disorder

The cancer story is even more provocative. Electrophysiological measurements across many cancer cell types reveal a consistent pattern: cancer cells are depolarized relative to healthy tissue. Quiescent, differentiated cells typically maintain membrane potentials between -50 mV and -90 mV. Tumor cells sit at much more positive voltages -10 mV to -30 mV.

Michael Levin’s lab demonstrated the causality of Vmem using Xenopus tadpoles. When they injected embryos with human oncogenes like mutant KRAS, Gli1, or p53, tumor-like structures formed in up to 50% of treated embryos. These structures exhibited all the hallmarks of tumors: overproliferation, lack of differentiation, attraction of vasculature, and histological disorganization. And they were depolarized. But after they have introduced hyperpolarizing ion channels into these embryos, tumor formation was significantly suppressed despite oncogene still being present at high levels in the cells. The genetic instruction to form a tumor was there. But the bioelectric state overrode it.

Conclusion

The genome dictates what programs are available. The bioelectric state tells the cell which program to run. There is no magic here. If you followed the argument above, this is exactly what you would expect from systems that maintain identity through their Markov blankets.

But I want to be clear about what this framework does and does not claim. Biology does not put all its eggs in one basket. A cell that relied solely on membrane potential for its decisions would be catastrophically fragile. Environmental noise, ion channel mutations, or simply thermal fluctuations could derail the organism entirely. Evolution has layered redundancy upon redundancy. Chemical gradients cross-check electrical signals, mechanical forces give spatial context, and gene regulatory networks buffer against transient perturbations. The bioelectric state is not a dictator that controls everything.

I do not believe that you can solve aging by simply hyperpolarizing cells. The practical question is rather what are the high leverage problems that could be solved with bioelectricity? As with the bone and tumor examples there are definitely contexts where bioelectric signals appear to be sufficient to tip the system towards a different attractor (new internal state through the Markov blanket interaction). Mapping these contexts and understanding which cellular decisions are electrically gated vs chemically or mechanically dominated is where a lot of interesting work lies.

We started with a question about how objects persist as distinguishable entities and ended with FDA approved bone stimulators and tumor suppression in tadpoles. The underlying principle that is unifying all this is the Markov blanket. The low dimensional boundary through which any system must perceive and act. Bioelectricity matters because it is a signal that in certain contexts we can easily measure, modulate, and propagate across tissues faster than the alternatives. And yet, the vast majority of bioelectric code has not been mapped.

But the point is not about bioelectricity specifically. It is about realizing that cells are not passive executors of genetic programs, but agents that update their behavior based on signals at their boundaries. Once you see biology this way, new intervention strategies are hiding in plain sight.

Thanks to Viraj Chhajed, Benjamin Anderson, Cameron Ferguson, Arsenii Litus, and Adar Kahiri for feedback on drafts of this essay.

Thank you to the author for an interesting article! Of course, its target audience is scientists and researchers, but even for people who are simply interested in the latest achievements in various fields of science (and I consider myself one of them), it was very informative and interesting. Especially the second part of the article, in which the author gives examples of how various external influences on cells can change their behavior and, as a result, change the behavior of the entire biological system. This is an inspiring and promising message. I look forward to the author's next series in this endless series of studies of cell biology.